CARL: Hi, come and take a seat.

JULIE: Thank you.

CARL: My name’s Carl Rogers and I’m one of the doctors here at the Total Health Clinic. So I understand this is your first visit to the clinic?

JULIE: Yes, it is.

CARL: OK, well I hope you’ll be very happy with the service you receive here. So if it’s alright with you I’ll take a few details to help me give you the best possible service.

JULIE: Sure.

CARL: So can I check first of all that we have the correct personal details for you? So your full name is Julie Anne (Example) Garcia?

JULIE: That’s correct.

CARL: Perfect. And can I have a contact phone number?

CARL: OK, and then can I just check that we have the correct date of birth?

CARL: Oh, I actually have 1991, I’ll just correct that now. Right, so that’s all good. Now I just need just a few more personal details … do you have an occupation, either full-time or part-time?

JULIE: Yes, I work full-time in Esterhazy’s – you know, the restaurant chain. I started off as a waitress there a few years ago and I’m a (Q3) manager now.

CARL: Oh I know them, yeah, they’re down on 114th Street, aren’t they?

JULIE: That’s right.

CARL: Yeah, I’ve been there a few times. I just love their salads.

JULIE: That’s good to hear.

CARL: Right, so one more thing I need to know before we talk about why you’re here, Julie, and that’s the name of your insurance company.

CARL: Excellent, thank you so much.

JULIE: Now Julie, let’s look at how we can help you. So tell me a little about what brought you here today.

JULIE: That’s certainly the right decision. So how long have you been aware of this pain? Is it just a few days, or is it longer than that?

CARL: Longer. It’s been worse for the last couple of days, but it’s (Q6) three weeks since I first noticed it. It came on quite gradually though, so I kind of ignored it at first.

JULIE: And have you taken any medication yourself, or treated it in anyway?

CARL: Yeah, I’ve been taking medication to deal with the pain. Tylenol, and that works OK for a few hours. But I don’t like to keep taking it.

JULIE: OK. And what about heat treatment? Have you tried applying heat at all?

CARL: No, but I have been using ice on it for the last few days.

JULIE: And does that seem to help the pain at all?

CARL: A little, yes.

JULIE: Good. Now you look as if you’re quite fit normally?

CARL: I am, yes.

JULIE: So do you do any sport on a regular basis?

CARL: Yes, I play a lot of (Q7) tennis. I belong to a club so I go there a lot. I’m quite competitive so I enjoy that side of it as well as the exercise. But I haven’t gone since this started.

JULIE: Sure. And do you do any other types of exercise?

CARL: Yeah, I sometimes do a little swimming, but usually just when I’m on vacation. But normally I go (Q8) running a few times a week, maybe three or four times.

JULIE: Hmm. So your legs are getting quite a pounding. But you haven’t had any problems up to now?

CARL: No, not with my legs. I did have an accident last year when I slipped and hurt my (Q9) shoulder, but that’s better now.

JULIE: Excellent. And do you have any allergies?

CARL: No, none that I’m aware of.

JULIE: And do you take any medication on a regular basis?

CARL: Well, I take (Q10) vitamins but that’s all. I’m generally very healthy.

JULIE: OK, well let’s have a closer look and see what might be causing this problem. If you can just get up …

SECTION 2

We’ll be arriving at Branley Castle in about five minutes, but before we get there I’ll give you a little information about the castle and what our visit will include.

So in fact there’s been a castle on this site for over eleven hundred years. The first building was a fort constructed in 914 AD for defence against Danish invaders by King Alfred the Great’s daughter, who ruled England at the time. In the following century, after the Normans conquered England, the land was given to a nobleman called Richard de Vere, and he built a castle there that stayed in the de Vere family for over four hundred years.

However, when Queen Elizabeth I announced that she was going to visit the castle in 1576 it was beginning to look a bit run down, and it was decided that rather than repair the guest rooms, (Q11) they’d make a new house for her out of wood next to the main hall. She stayed there for four nights and apparently it was very luxurious, but unfortunately it was destroyed a few years later by fire.

In the seventeenth century the castle belonged to the wealthy Fenys family, who enlarged it and made it more comfortable. However, by 1982 the Fenys family could no longer afford to maintain the castle, even though they received government support, and they put it on the market. It was eventually taken over by (Q12) a company who owned a number of amusement parks, but when we get there I think you’ll see that they’ve managed to retain the original atmosphere of the castle.

When you go inside, you’ll find that in the state rooms (Q13) there are life-like moving wax models dressed in costumes of different periods in the past, which even carry on conversations together. As well as that, in every room there are booklets giving information about what the room was used for and the history of the objects and furniture it contains.

The castle park’s quite extensive. At one time sheep were kept there, and in the nineteenth century the owners had a little zoo with animals like rabbits and even a baby elephant. Nowadays the old zoo buildings are used for (Q14) public displays of painting and sculpture. The park also has some beautiful trees, though the oldest of all, which dated back 800 years, was sadly blown down in 1987.

Now, you’re free to wander around on your own until 4.30, but then at the end of our visit we’ll all meet together at the bottom of the Great Staircase. We’ll then go on to the long gallery, where there’s a wonderful collection of photographs showing the family who owned the castle a hundred years ago having tea and cakes in the conservatory – and we’ll then take you to (Q15) the same place, where afternoon tea will be served to you.

——————————-

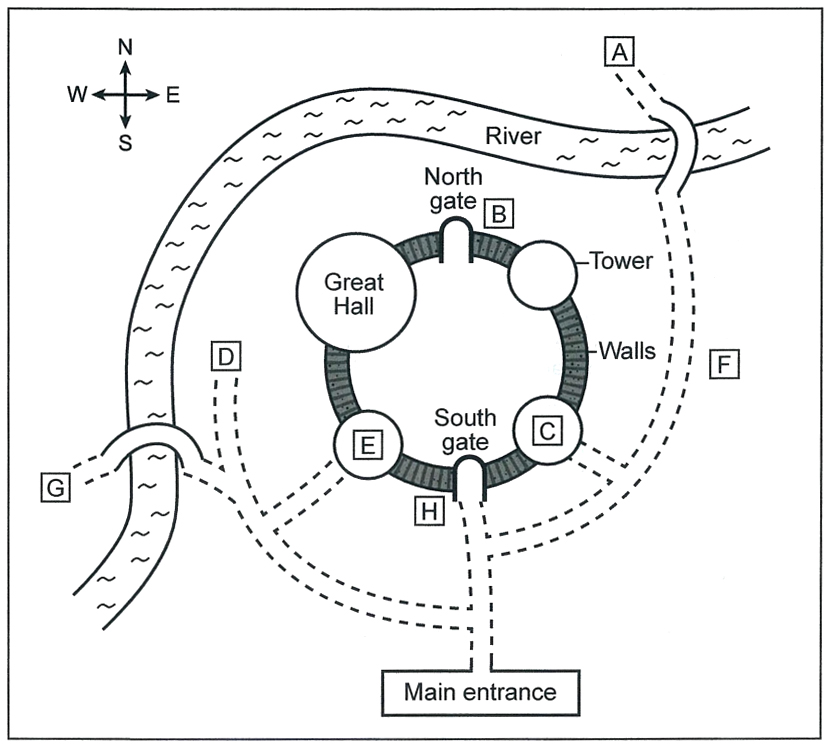

Now if you can take a look at your plans you’ll see Branley Castle has four towers, joined together by a high wall, with the river on two sides.

Don’t miss seeing the Great Hall. That’s near the river in the main tower, the biggest one, which was extended and redesigned in the eighteenth century.

If you want to get a good view of the whole castle, you can walk around the walls. (Q16) The starting point’s quite near the main entrance – walk straight down the path until you get to the south gate, and it’s just there. Don’t go on to the north gate – there’s no way up from there.

There’ll shortly be a show in which you can see archers displaying their skill with a bow and arrow. The quickest way to get there is to (Q17) take the first left after the main entrance and follow the path past the bridge, then you’ll see it in front of you at the end.

If you like animals there’s also a display of hunting birds – falcons and eagles and so on. If you (Q18) go from the main entrance in the direction of the south gate, but turn right before you get there instead of going through it, you’ll see it on your right past the first tower.

At 3 pm there’s a short performance of traditional dancing on the (Q19) outdoor stage. That’s right at the other side of the castle from the entrance, and over the bridge. It’s about ten minutes’ walk or so.

And finally the shop. It’s actually (Q20) inside one of the towers, but the way in is from the outside. Just take the first left after the main entrance, go down the path and take the first right. It’s got some lovely gifts and souvenirs.

Right, so we’re just arriving …

SECTION 3

TUTOR: So, Rosie and Martin, let’s look at what you’ve got for your presentation on woolly mammoths.

ROSIE: OK, we’ve got a short outline here.

TUTOR: Thanks. So it’s about a research project in North America?

MARTIN: Yes. But we thought we needed something general about woolly mammoths in our introduction, to establish that they were related to our modern elephant, and they lived thousands of years ago in the last ice age.

ROSIE: Maybe we could show a video clip of a cartoon about mammoths. But that’d be a bit childish. Or we could have a diagram, (Q21) it could be a timeline to show when they lived, with illustrations?

MARTIN: Or we could just show a drawing of them walking in the ice? No, let’s go with your last suggestion.

TUTOR: Good. Then you’re describing the discovery of the mammoth tooth on St Paul’s Island in Alaska, and why it was significant.

ROSIE: Yes. The tooth was found by a man called Russell Graham. He picked it up from under a rock in a cave. He knew it was special – for a start it was in really good condition, as if it had been just extracted from the animal’s jawbone. Anyway, they found it was 6,500 years old.

TUTOR: So why was that significant?

ROSIE: Well (Q22) the mammoth bones previously found on the North American mainland were much less recent than that. So this was really amazing.

MARTIN: Then we’re making an animated diagram to show the geography of the area in prehistoric times. So originally, St Paul’s Island wasn’t an island, it was connected to the mainland, and mammoths and other animals like bears were able to roam around the whole area.

ROSIE: Then the climate warmed up and the sea level began to rise, and the island got cut off from the mainland. So (Q23) those mammoths on the island couldn’t escape; they had to stay on the island.

MARTIN: And in fact the species survived there for thousands of years after they’d become extinct on the mainland.

TUTOR: So why do you think they died out on the mainland?

ROSIE: No one’s sure.

MARTIN: Anyway, next we’ll explain how Graham and his team identified the date when the mammoths became extinct on the island. They concluded that (Q24) the extinction happened 5,600 years ago, which is a very precise time for a prehistoric extinction. It’s based on samples they took from mud at the bottom of a lake on the island. They analysed it to find out what had fallen in over time – bits of plants, volcanic ash and even DNA from the mammoths themselves. It’s standard procedure, but it took nearly two years to do.

————————-

TUTOR: So why don’t you quickly go through the main sections of your presentation and discuss what action’s needed for each part?

MARTIN: OK. So for the introduction, we’re using a visual, so once we’ve prepared that we’re done.

ROSIE: I’m not sure. I think (Q25) we need to write down all the ideas we want to include here, not just rely on memory. How we begin the presentation is so important …

MARTIN: You’re right.

ROSIE: The discovery of the mammoth tooth is probably the most dramatic part, but we don’t have that much information, only what we got from the online article. I thought maybe (Q26) we could get in touch with the researcher who led the team and ask him to tell us a bit more.

MARTIN: Great idea. What about the section with the initial questions asked by the researchers? We’ve got a lot on that but we need to make it interesting.

ROSIE: We could (Q27) ask the audience to suggest some questions about it and then see how many of them we can answer. I don’t think it would take too long.

TUTOR: Yes that would add a bit of variety.

MARTIN: Then the section on further research carried out on the island – analysing the mud in the lake. I wonder if we’ve actually got too much information here, should we cut some?

ROSIE: I don’t think so, but it’s all a bit muddled at present.

MARTIN: Yes, (Q28) maybe it would be better if it followed a chronological pattern.

ROSIE: I think so. The findings and possible explanations section is just about ready, but we need to practice it (Q29) so we’re sure it won’t overrun.

MARTIN: I think it should be OK, but yes, let’s make sure.

TUTOR: In the last section, relevance to the present day, you’ve got some good ideas but this is where you need to move away from the ideas of others and (Q30) give your own viewpoint.

MARTIN: OK, we’ll think about that. Now shall we …

SECTION 4

In this series of lectures about the history of weather forecasting, I’ll start by examining its early history – that’ll be the subject of today’s talk.

Ok, so we’ll start by going back thousands of years. Most ancient cultures had weather gods, and weather catastrophes, such as floods, played an important role in many creation myths. Generally, weather was attributed to the whims of the gods, as the wide range of weather gods in various cultures shows. For instance, there’s the Egyptian sun god Ra, and Thor, the Norse god of thunder and lightning. Many ancient civilisations developed rites such as (Q31) dances in order to make the weather gods look kindly on them.

But the weather was of daily importance: observing the skies and drawing the correct conclusions from these observations was really important, in fact their (Q32) survival depended on it. It isn’t known when people first started to observe the skies, but at around 650 BC, the Babylonians produced the first short-range weather forecasts, based on their observations of (Q33) clouds and other phenomena. The Chinese also recognised weather patterns, and by 300 BC, astronomers had developed a calendar which divided the year into 24 (Q34) festivals, each associated with a different weather phenomenon.

The ancient Greeks were the first to develop a more scientific approach to explaining the weather. The work of the philosopher and scientist Aristotle, in the fourth century BC, is especially noteworthy, as his ideas held sway for nearly 2,000 years. In 340 BC, he wrote a book in which he attempted to account for the formation of rain, clouds, wind and storms. He also described celestial phenomena such as haloes – that is, bright circles of light around the sun, the moon and bright stars – and (Q35) comets. Many of his observations were surprisingly accurate. For example, he believed that heat could cause water to evaporate. But he also jumped to quite a few wrong conclusions, such as that winds are breathed out by the Earth. Errors like this were rectified from the Renaissance onwards.

———————–

For nearly 2,000 years, Aristotle’s work was accepted as the chief authority on weather theory. Alongside this, though, in the Middle Ages weather observations were passed on in the form of proverbs, such as ‘Red (Q36) sky at night, shepherd’s delight; red sky in the morning, shepherd’s warning’. Many of these are based on very good observations and are accurate, as contemporary meteorologists have discovered.

For centuries, any attempt to forecast the weather could only be based on personal observation, but in the fifteenth century scientists began to see the need for (Q37) instruments. Until then, the only ones available were weather vanes – to determine the wind direction – and early versions of rain gauges. One of the first, invented in the fifteenth century, was a hygrometer, which measured humidity. This was one of many inventions that contributed to the development of weather forecasting.

In 1592, the Italian scientist and inventor Galileo developed the world’s first (Q38) thermometer. His student Torricelli later invented the barometer, which allowed people to measure atmospheric pressure. In 1648, the French philosopher Pascal proved that pressure decreases with altitude. This discovery was verified by English astronomer Halley in 1686, and Halley was also the first person to map trade winds.

This increasing ability to measure factors related to weather helped scientists to understand the atmosphere and its processes better, and they started collecting weather observation data systematically. In the eighteenth century, the scientist and politician Benjamin Franklin carried out work on electricity and lightning in particular, but he was also very interested in weather and studied it throughout most of his life. It was Franklin who discovered that (Q39) storms generally travel from west to east.

In addition to new meteorological instruments, other developments contributed to our understanding of the atmosphere. People in different locations began to keep records, and in the mid-nineteenth century, the invention of the (Q40) telegraph made it possible for these records to be collated. This led, by the end of the nineteenth century, to the first weather services.

It was not until the early twentieth century that mathematics and physics became part of meteorology, and we’ll continue from that point next week.